![]()

I spent a week in early April of 1998 riding dual-suspended bikes in and around Bradford-on-Avon, England, where Alex Moulton lived and where his revolutionary Moulton bicycles are built.

There are canals in this part of England that people traverse in houseboats (sort of like floating RVs). Next to the canals are gravel paths called towpaths because at one time horses walked there pulling the boats. Today, these towpaths are a great place to cycle if they happen to go your way. And when they don’t, you can always find beautiful stone wall–lined country lanes to follow. Due to their bumpy nature, the paths and lanes are a perfect place to pedal on a bicycle with built in shock absorbers front and rear.

England's idyllic cycleways. While the surface is unpaved, it’s packed so well that rain doesn't turn it gooey

Suspension for the street

Why test dual suspension anywhere but on the side of a mountain, you ask? Because I was riding a road bike. We tend to think of suspension as a relatively new phenomenon brought to us by mountain-bike innovators. So it may be surprising to learn that Alex Moulton has been working on bicycle suspension since 1956, when gasoline was rationed in England and he took up pedaling to cut fuel usage. Finding the conventional bike limited and uncomfortable, he did what any engineer might do: he began reinventing it.

Moulton’s experience was in building automobile suspensions. A descendant of a family of rubber technologists, he developed new car and truck suspensions that incorporated rubber. These are still used today in cars such as the Mini, MG and Land Rover.

Coming from an automobile background it was only natural for Moulton to question the need for large wheels on a bike. He knew that smaller wheels offered advantages such as less weight, better acceleration, allowing a lower frame design that could be used by men and women (even children) and that loads over the wheels would be carried lower for better stability (and that more gear would fit by utilizing the space over the wheels). Of course, he also recognized that smaller wheels would yield a harsh ride. But he had a great solution: suspension (shock absorbers).

Views at the Moulton museum. Some of these designs date to the 1950s, such as the red aluminum monocoque (below)

Mini wheels and cloud-like comfort

In 1963, the first Moultons were produced. Startlingly unique at the time, they featured 16-inch wheels with a wonderfully soft ride thanks to a telescopic-suspension (coil spring and rubber) front fork and a rubber-sprung rear end. The bike was super versatile because the same frame fit most riders (child to adult), meaning one bike could work for the entire family. There were also integral and instant-on/off racks with handy baskets and bags, making it simple to carry all loads. Plus, you could disassemble the frame (on certain models) for toting a bike (even two) in the trunk of the smallest car. Ingeniously, there was even a handle built into the frame at the exact balance point, so carrying the bike up and down stairs (or perhaps to get on a bus) was a breeze.

Moultons offer ample carrying capacity and front and rear racks that can be installed and removed in seconds. Shown is a 1969 Speed (the carrying "handle" is the horizontal frame tube just above the left pedal)

British great Tommy Simpson racing his Speed graces the Moulton factory (at the left of the turret in the next picture)

Sales of the bikes took off to the tune of 150,000 units in their heyday, which prompted Raleigh to purchase the design and begin producing numerous knock-off small-wheel and folding bikes. In the 1980s Moulton came out with a new design with all the features of the first bikes but based on a space frame built with small-diameter Reynolds tubing. And in the 1990s, he worked with British producer Pashley to introduce a Moulton called the APB (All Purpose Bicycle) with 20-inch wheels and a lower price.

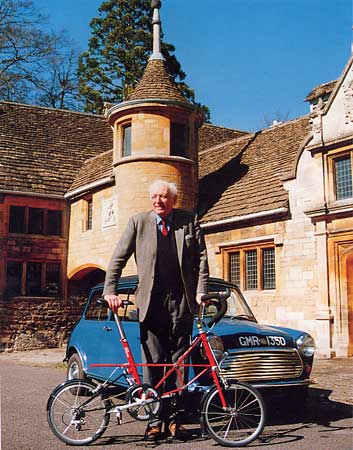

Alex posing with an AM series bike and Mini in front of the carriage shed, where Moultons are built

Brilliant debut

But that’s old news. What brought me to England was to see Moulton’s latest creation: the New Series Moulton. I wanted to be there because it’s amazing to me that at 78 years old (he was born April 9, 1920), Alex is still driven to refine his design and improve cycling. I missed the first introduction of his bike (I was ten years old). I didn’t want to miss this one.

The debut took place at the Royal College of Art in London, a fitting location for the unveiling of the result of a life’s work. True to previous designs, the New Series sports all the features expected of a Moulton. The take-apart (it now separates into more pieces to fit in the smallest case yet) unisex space frame is there in either Reynolds 531 or aerospace-grade stainless-steel tubing. The small wheels are now built around a 406 rim, which solves one of the main problems with past Moultons, some of which used a proprietary tire size available only from Moulton. Now lots of tires can be used.

Shimano’s Dura-Ace crank, brake calipers, pedals, 10-speed cassette and derailleur are used. The large-diameter seatpost is now titanium (and yes, as with former Moultons, a pump is stored inside). The hubs are British-made Gold Tecs, and the spacing is non-standard at 70mm front, 120mm rear. Total bike weight is about 22 pounds. (Note: Specs will change year to year.)

The best suspension yet

Most impressive is the new Flexitor front suspension, which is the most active I’ve experienced. The spring medium is rubber in torsion, which promises long life, little maintenance if any, and zero stiction. As the suspension is compressed, resistance is created by rubber pieces that are bonded inside the crossmembers of the fork legs. As the legs move, the bars twist and the rubber resists, providing the spring. You’ve got to feel it to believe it. I rode with one hand on the bar and rested a finger of my other hand on the forward crossbrace. Even on smooth pavement, while my hand on the bar felt absolutely no buzzing or bumps, the suspension moved furiously like the needle on a sewing machine.

Suspension this active may bug someone who muscles over the hills, because it can bob. For this type of rider, there’s a soft lockout that can be engaged and released easily while riding, though you do have to reach down. This prevents most of the suspension movement while still providing shock absorption on bigger bumps.

There’s also a second stage to the fork. A rubber bumper kicks in when the fork is bottomed on a big hit, which comes in handy for heavier riders. Plus the fork has an anti-dive feature, meaning it isn’t activated by braking forces.

Moulton’s Flexitor fork (above left) and Hydrolastic rear

shock (below) take all the abuse out of rough roads. For out-of-the-saddle climbing, use the manual soft lockout, which prevents

bobbing (above right).

For out-of-the-saddle climbing, use the manual soft lockout, which prevents

bobbing (above right).

High-tech Hydrolastic rear shock

Though it looks more conventional than the front fork, the new Hydrolastic rear shock unit now offers adjustable liquid damping so you can tune the feel. This improves ride quality but still feels similar to past Moulton rear suspensions. Interestingly the bike uses a unified-rear-triangle design to eliminate all suspension-induced pedal movement.

Another innovation is a new handlebar called the Mosquito. Moultons use

an adjustable stem, which can be moved to put the rider as high or low or

as stretched out or compact as she likes with the turn of an Allen wrench.

The Mosquito bars can also be rotated to provide a racing or touring position.

Another innovation is a new handlebar called the Mosquito. Moultons use

an adjustable stem, which can be moved to put the rider as high or low or

as stretched out or compact as she likes with the turn of an Allen wrench.

The Mosquito bars can also be rotated to provide a racing or touring position.

They’re

narrow because Moulton believes thoroughly in providing an aero rider profile

to the wind. I found them slightly too narrow when standing on steep hills.

They were comfortable enough when seated and a slightly wider version is

available. It’s also a simple matter to swap for either flat or drop bars

if you like. I especially liked the new brake levers, a German design that’s

adjustable for all hand sizes and includes a parking-brake feature.

They’re

narrow because Moulton believes thoroughly in providing an aero rider profile

to the wind. I found them slightly too narrow when standing on steep hills.

They were comfortable enough when seated and a slightly wider version is

available. It’s also a simple matter to swap for either flat or drop bars

if you like. I especially liked the new brake levers, a German design that’s

adjustable for all hand sizes and includes a parking-brake feature.

Moulton’s New Series bikes are intended to be extremely limited production, a best-of-the-best hand-produced custom product, if you will. They’re built in a small shop on Moulton’s estate by craftsmen, some of whom have been building Moultons for decades. Consequently and appropriately, the New Series sells for a dear price. But, if you’re looking for a one-of-a-kind, incredibly versatile dual-suspended road bike, hand-built by a legend in cycling, there’s really no equivalent.

Visit the site of Moulton Bicycles; you’ll also enjoy Moulton expert Tony Hadland.