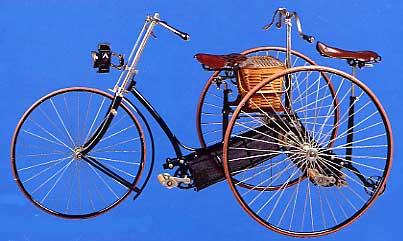

This superb 1889 Rudge adult tandem tricycle sold for $17,000.  Notice the tiny steel wheelie wheel just behind the rear seat tube and the coasting pegs on the fork. And, how ’bout that handy wicker basket; picnic anyone? April 5, the day before the Schwinn-family bicycle collection auction, I met Jerry Rodman. We bumped into each other at the exhibition where you get a chance to study the stuff up close. The gallery is in downtown Chicago, not far from where Schwinns were built for almost a hundred years. I

spent three hours sorting through turn-of-the-century bicycle catalogs,

gawking at display cases full of nameplates

("head badges"), handling bicycle miniatures, thumbing through

libraries full of long-out-of-print cycling titles, and drooling over

the 150 spectacular bicycles to be auctioned. Rodman was just standing

there, looking melancholy. Then

with the recall of a nine-year-old he told me about racing six-days for

Schwinn. It was during the 1930s, the heyday of the race game, when cycling

was to American sport what baseball is today. Six-day

races are just that, grueling marathons held on a track, crowds sometimes

swelling to 25,000 at the height of the action. Take

the 1968 Sting-Ray Orange Krate, the one-millionth to roll off Schwinn’s

assembly line, that sold for $16,100; the 1960 Bowden

Spacelander that fetched $19,500, and the money-maker of the day,

a 1869 Dexter boneshaker made in Poughkeepsie, New York, that netted $24,150.  1869 Dexter, $24,150! Among the earliest bikes, “boneshakers” got their unflattering name  because of the way the steel “tires” rattle down the road. On today’s roads, they shake your fillings loose and slide in corners. The bikes raised $700,000, twice what Leslie Hindman, who owns the auction house, expected.  Late 1870s Shire, $17,000. This unusual boneshaker was made in Detroit,  mostly of wood. Note the triangular pedals. |